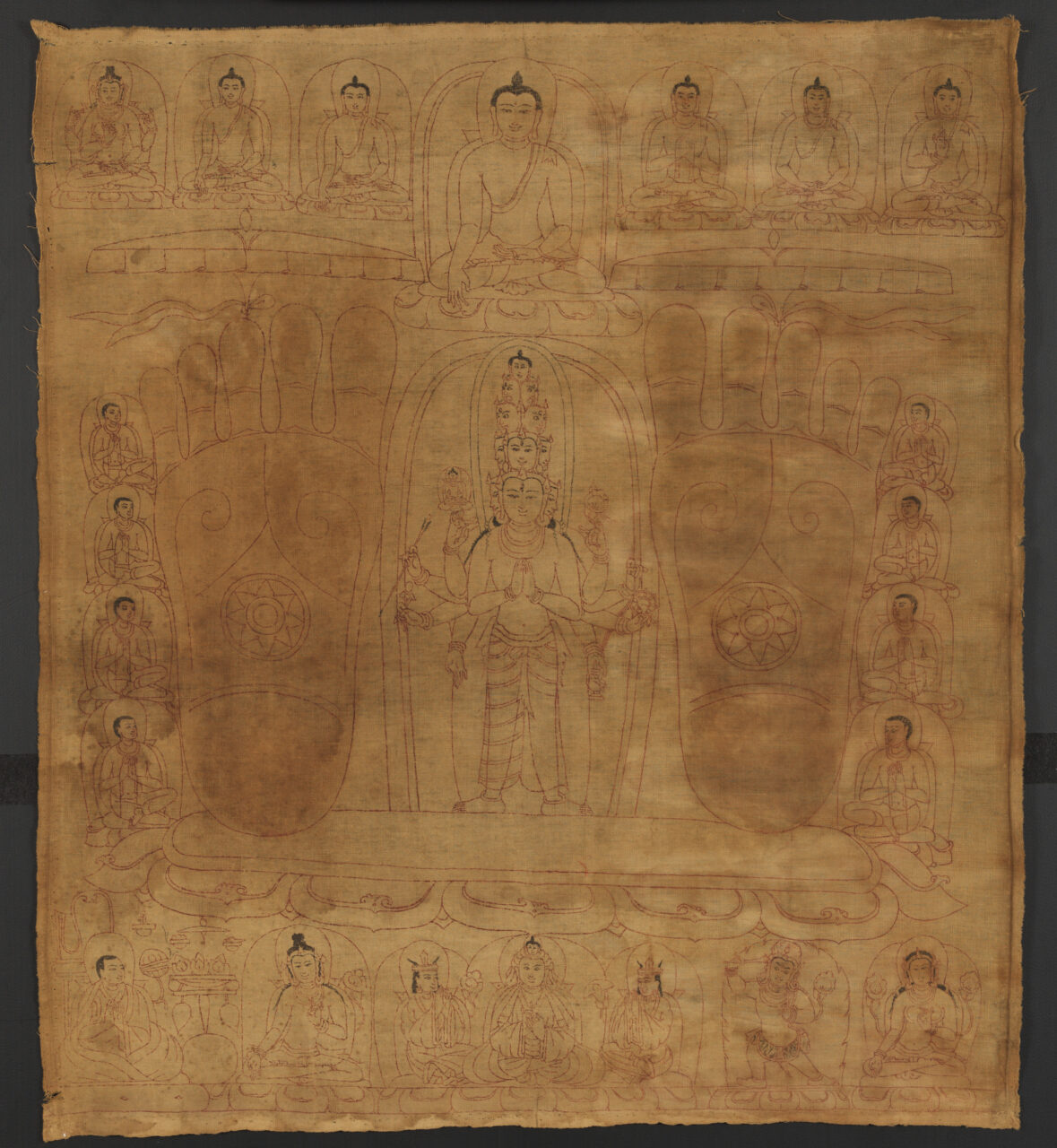

Different Asian religious traditions posit different types of divine beings. Hindus generally believe in an all-encompassing God-like being, called Brahman. They also believe in a variety of other gods (deva), including Brahma, Vishnu, and Shiva. Early Buddhists denied the existence of a single, all-powerful creator god. Nevertheless, they always recognized a variety of powerful spirits, like gandharvas and nagas. Mahayana Buddhists came to see bodhisattvas as beings of enormous power, and buddhas themselves as cosmic beings with the ability to create entire universes. Buddhist and Bon traditions in Tibet worshiped a variety of other gods (Tib. lha), like the mountain gods, or gods of the land. According to Buddhist tradition, enlightened deities are seen as beyond the cycle of death and rebirth, whereas gods (including Hindu gods) are not.

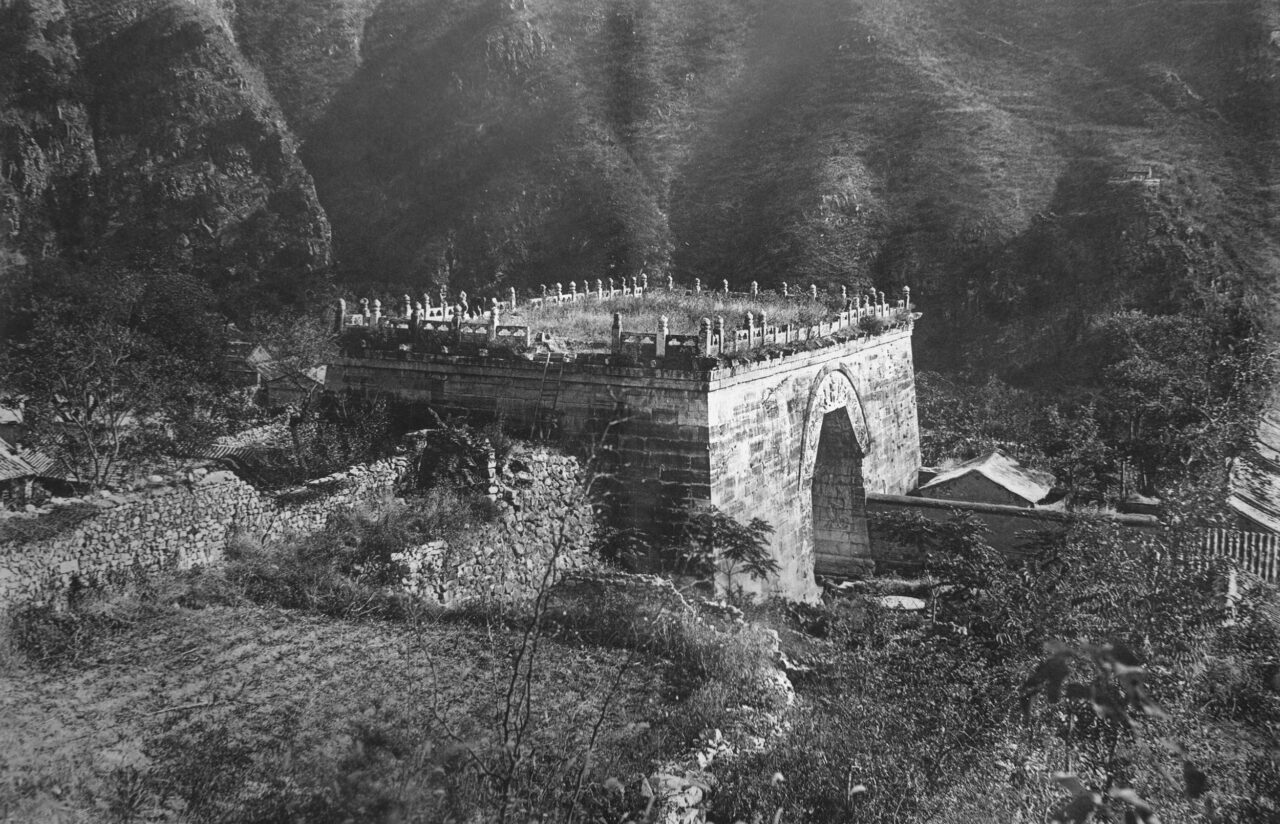

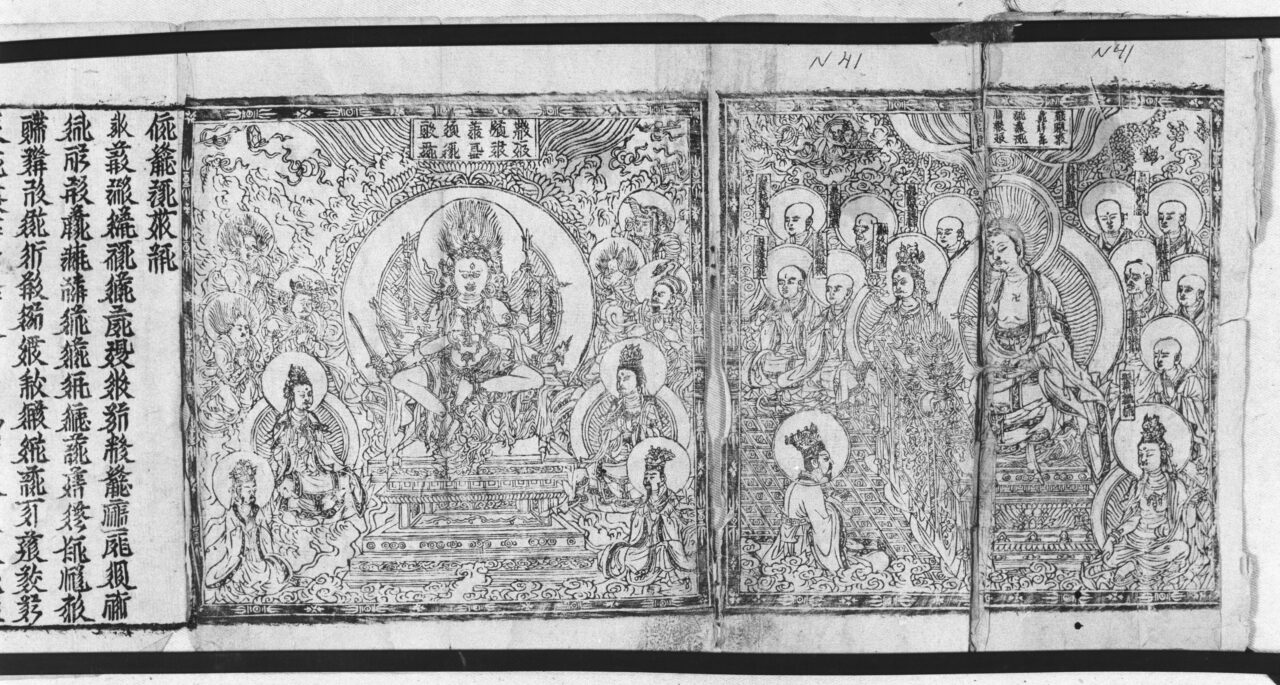

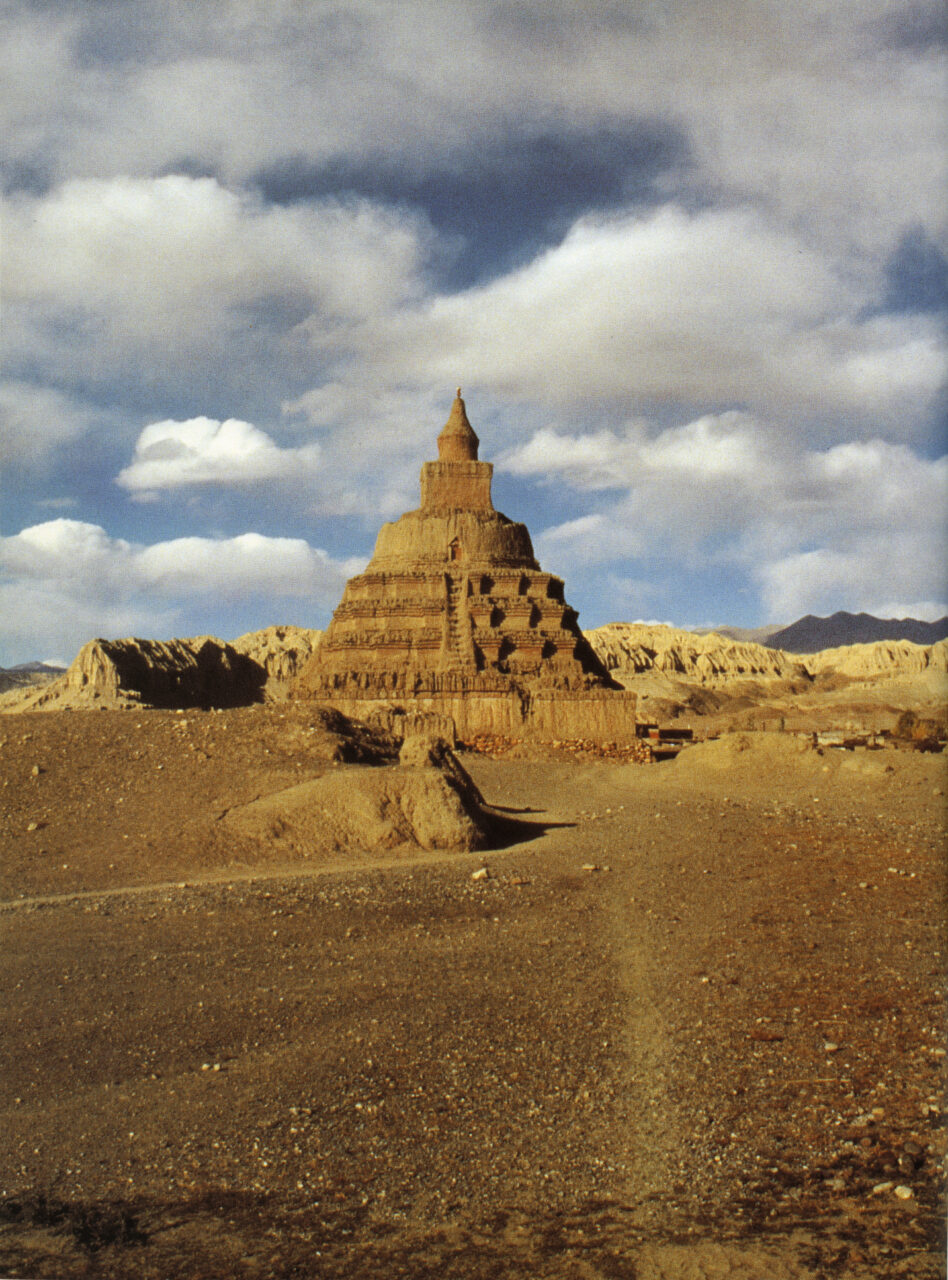

The Tanguts were an ethnic group in medieval East-Central Asia, who called themselves Minyak and spoke a language distantly related to Tibetan. Between 1038 and 1227 CE the Tanguts ruled a state in what is now the Chinese provinces of Ningxia, Gansu, and Qinghai. This state took the Chinese dynastic name of Xia, also called Xixia “Western Xia.” The Tangut-Xixia emperors were major patrons of Buddhism, inviting both Chinese and Tibetan monks to teach in the capital, and instituting major Buddhist translation and printing projects in three languages. The Tangut state was destroyed by the armies of Chinggis Khan, leading to their absorption into the Mongol Empire, where many Tanguts served as officials.

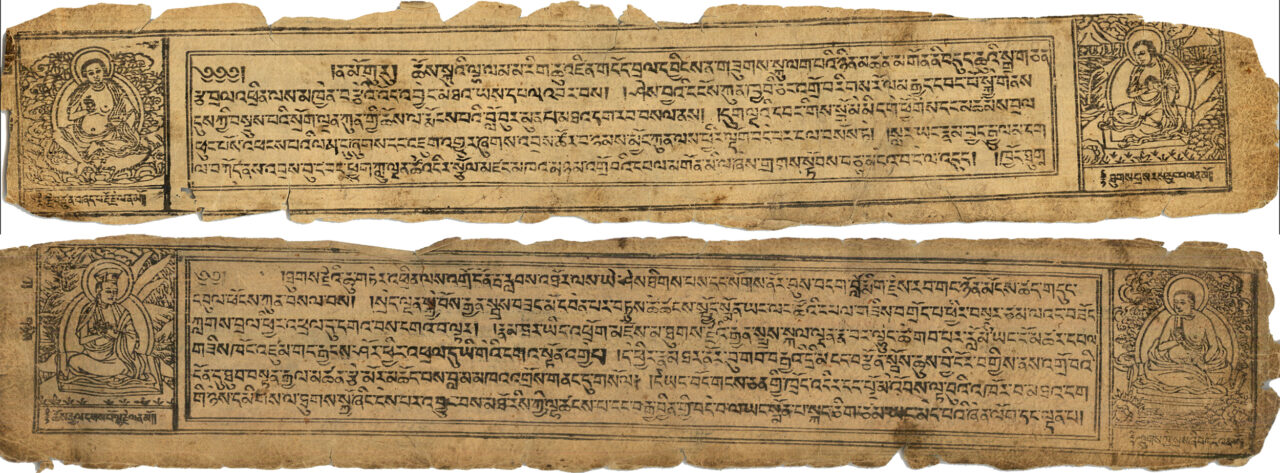

The Tibetan script is used to write the Tibetan language, as well as several other smaller Himalayan languages. Based on the Brahmi script used in the Gupta Empire in India, the Tibetan script was developed under the Tibetan Empire in the seventh century and is credited to minister Tonmi Sambhota (b. 619?). Two important forms of the Tibetan script are “Uchen” (Tib. “having a head”), a standard type used in printed texts, and “Umey” (Tib. “headless”), a cursive form sometimes used in manuscripts. There are many other cursive and decorative forms of the script.

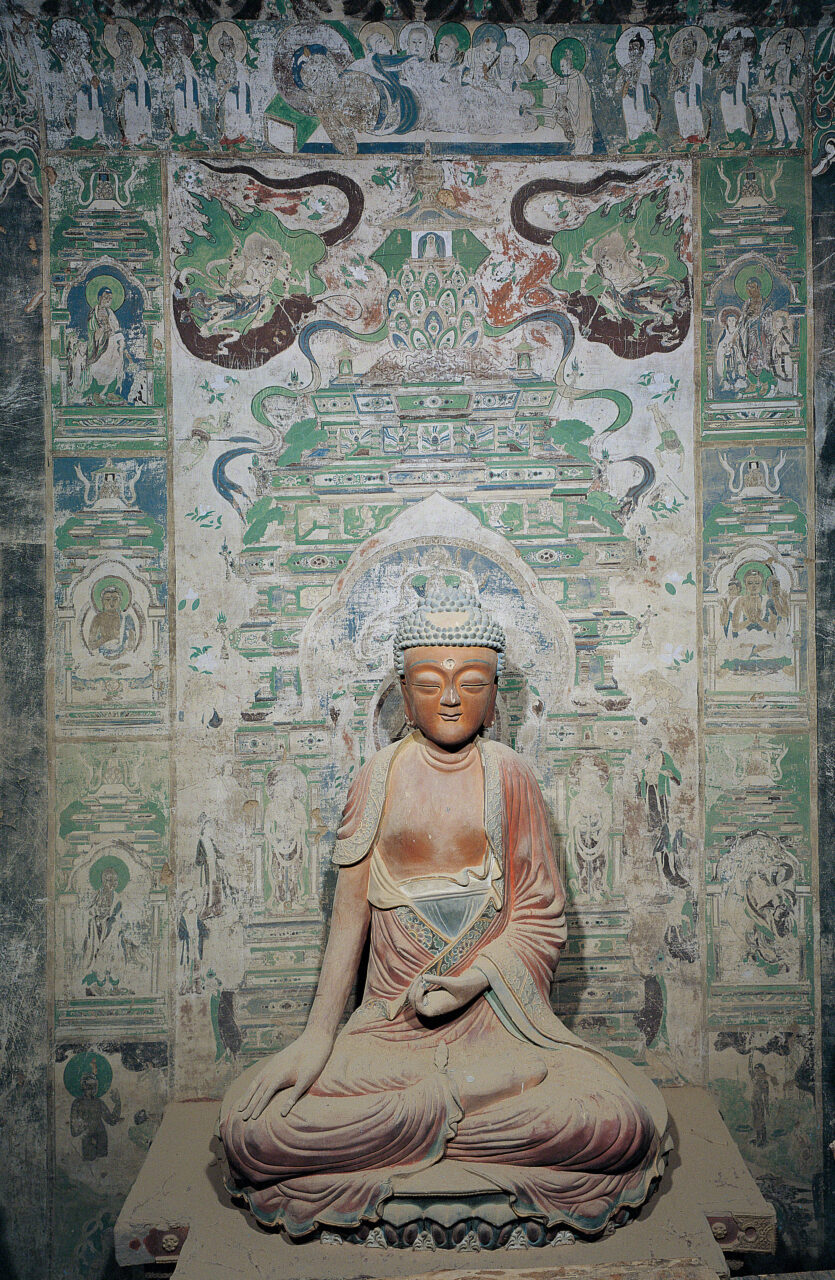

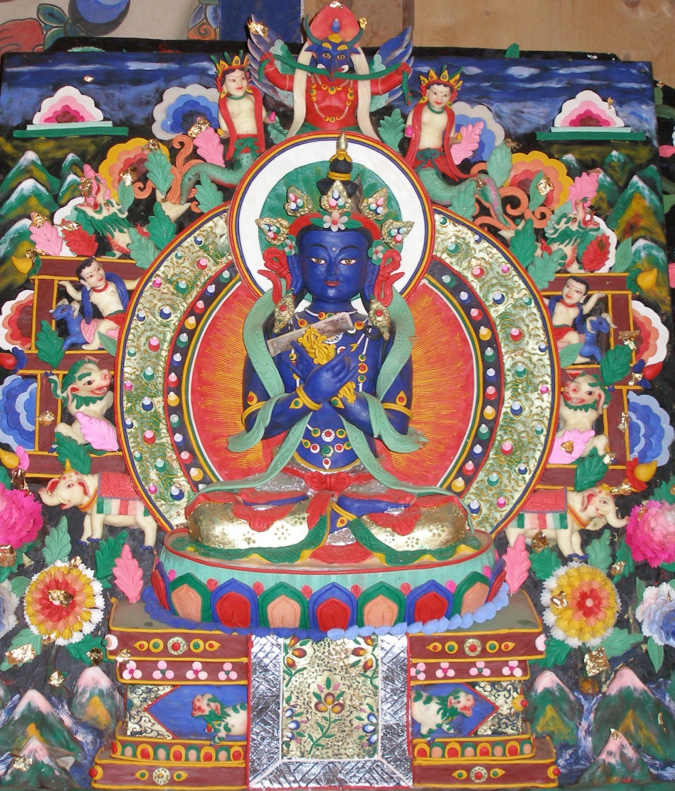

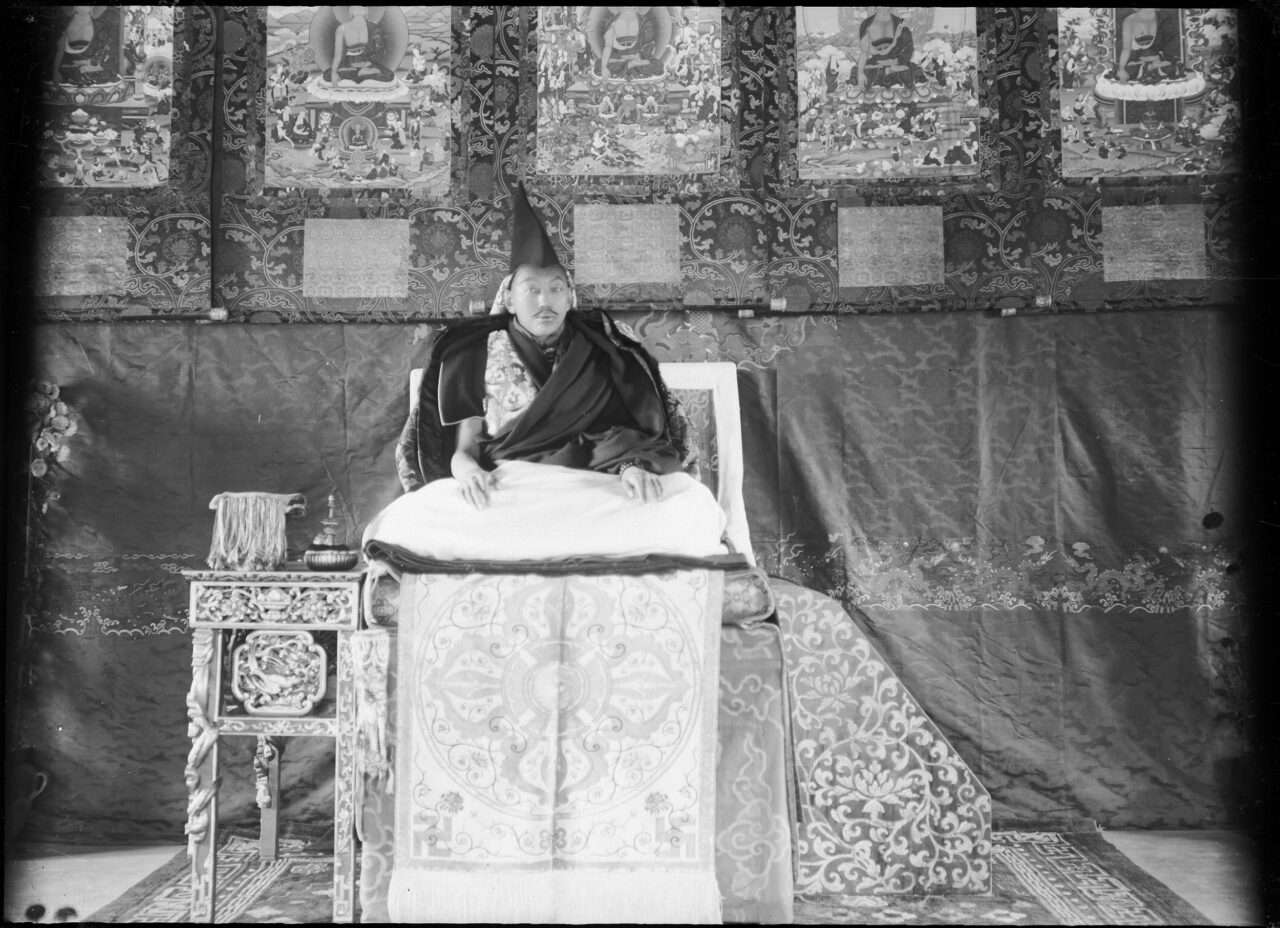

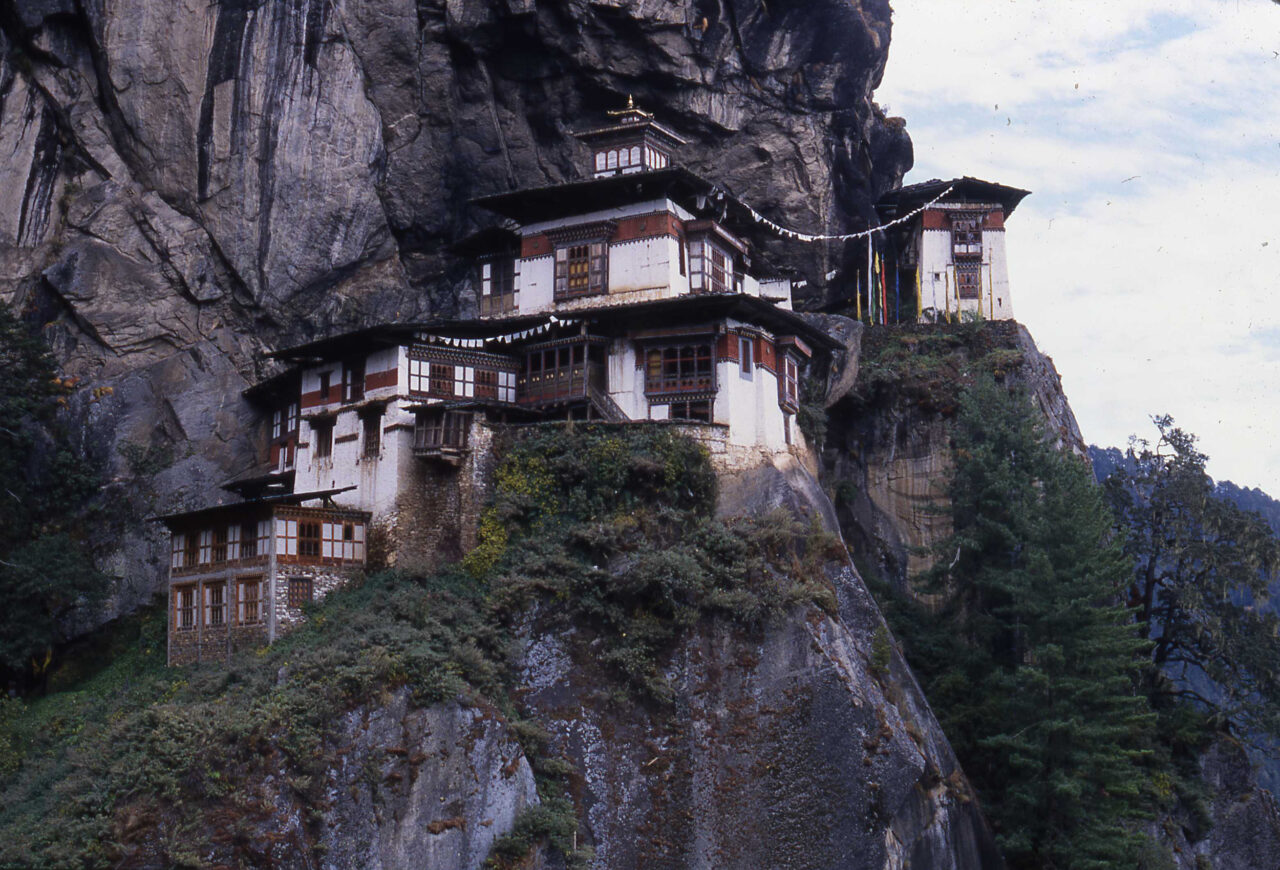

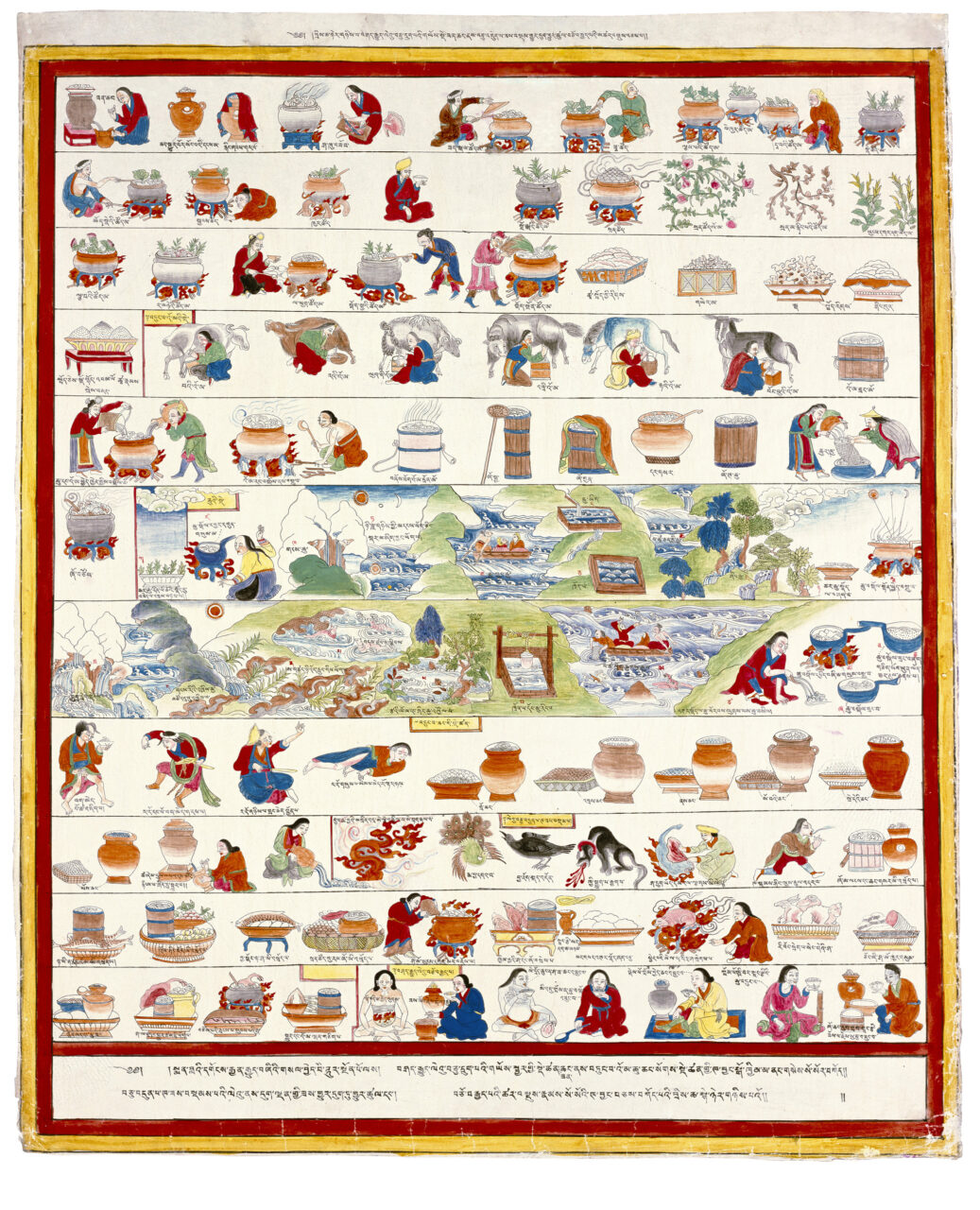

Historically, Tibetan Buddhism refers to those Buddhist traditions that use Tibetan as a ritual language. It is practiced in Tibet, Mongolia, Bhutan, Ladakh, and among certain groups in Nepal, China, and Russia and has an international following. Buddhism was introduced to Tibet in two waves, first when rulers of the Tibetan Empire (seventh to ninth centuries CE), embraced the Buddhist faith as their state religion, and during the second diffusion (late tenth through thirteenth centuries), when monks and translators brought in Buddhist culture from India, Nepal, and Central Asia. As a result, the entire Buddhist canon was translated into Tibetan, and monasteries grew to become centers of intellectual, cultural, and political power. From the end of the twelfth century, Tibetans were exporting their own Buddhist traditions abroad. Tibetan Buddhism integrates Mahayana teachings with the esoteric practices of Vajrayana, and includes those developed in Tibet, such as Dzogchen, as well as indigenous Tibetan religious practices focused on local gods. Historically major traditions of Tibetan Buddhism are Nyingma, Kagyu, Sakya, and Geluk.

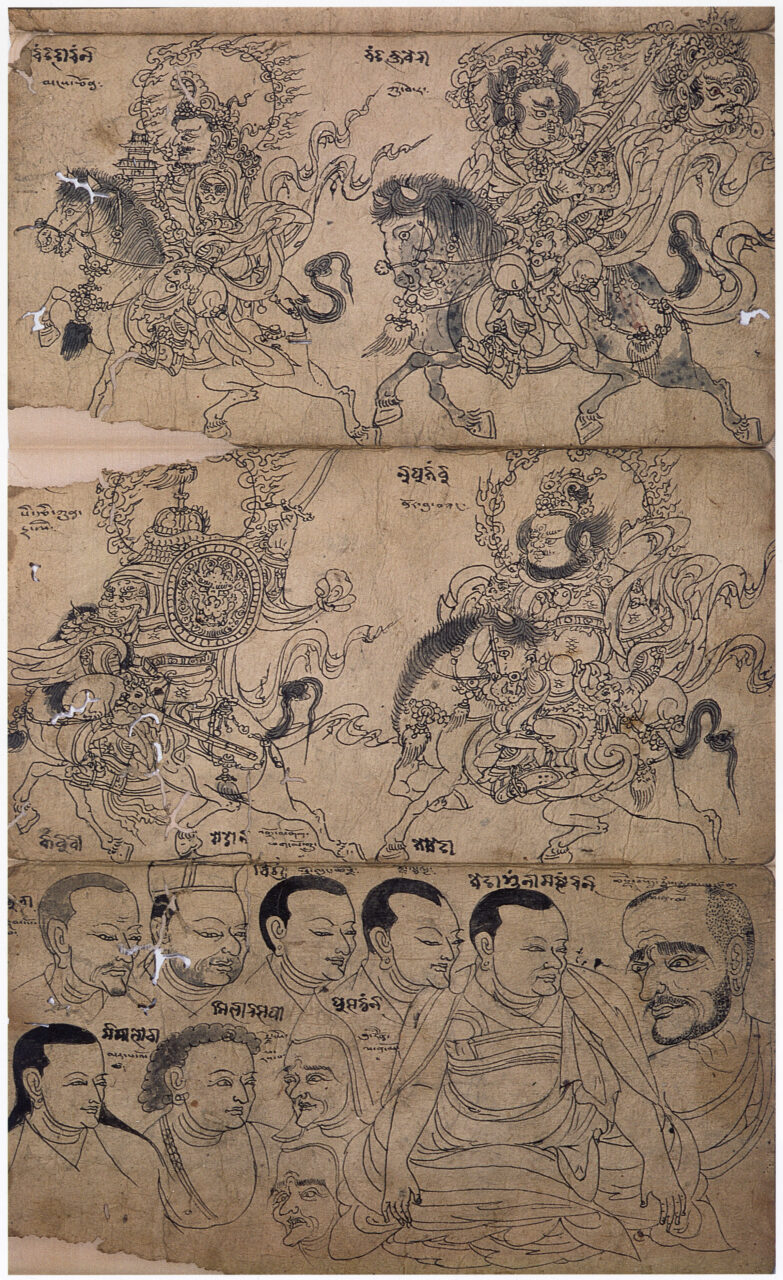

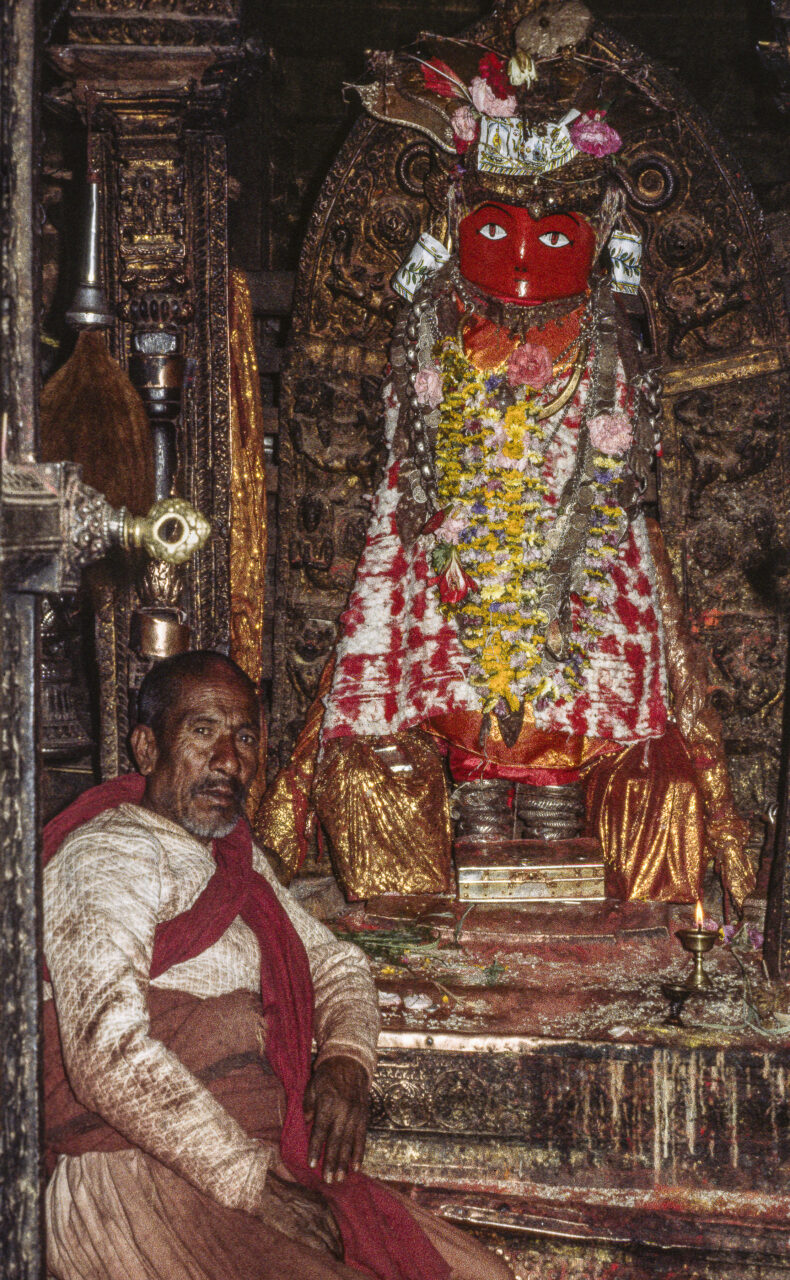

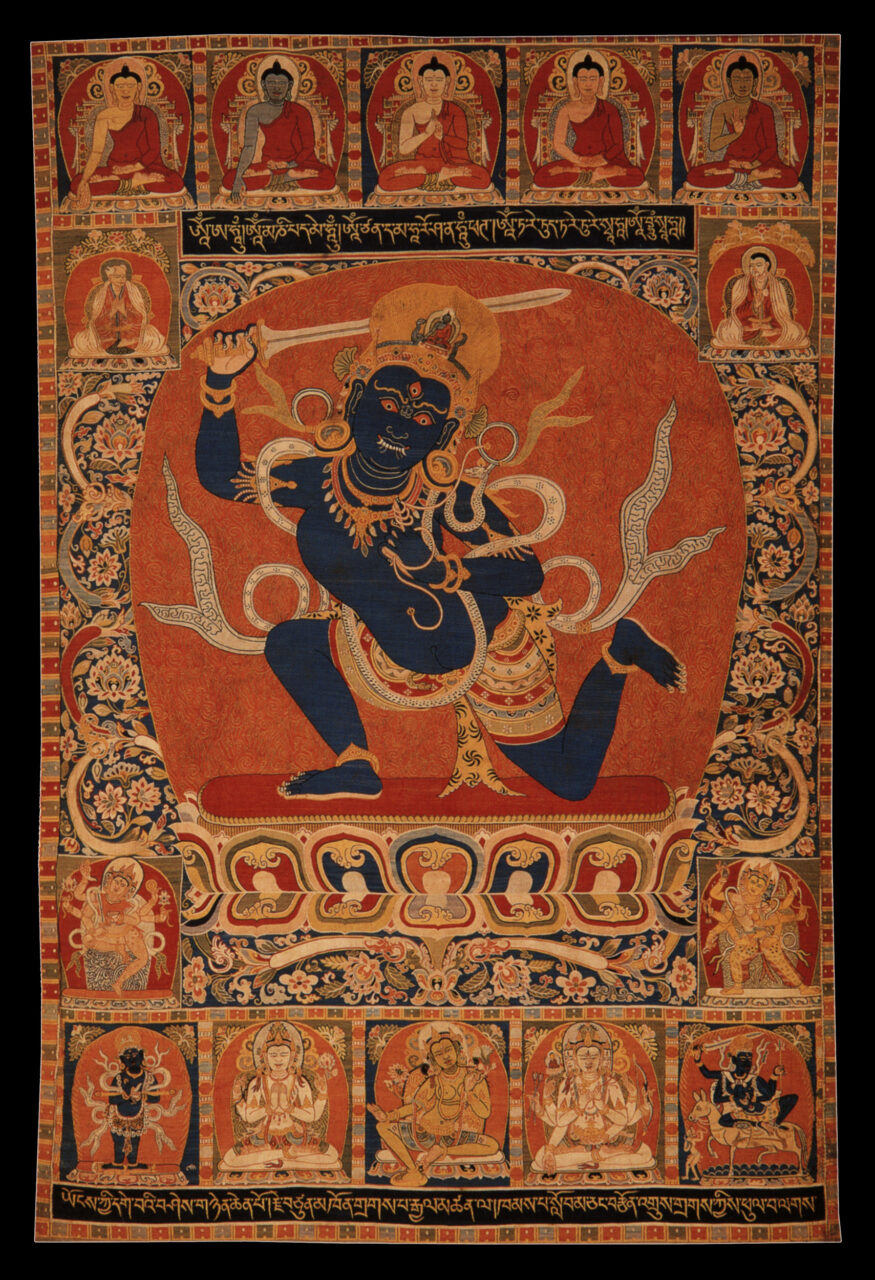

In Hinduism, Buddhism, and Bon, some gods and deities are shown with flaming hair, bulging eyes, mouths showing fangs, adorned with garlands of severed heads, and trampling enemies, real or metaphorical. In Tantric Buddhism, such deities are said to be wrathful manifestations of wisdom and method who assume fierce appearance to protect, remove or overcome mental afflictions blocking the path to enlightenment. Others are unenlightened, indigenous gods bound by oath to protect Buddhist traditions. Some female deities, or dakinis, like Vajrayogini, appear as semi-wrathful, in beatific form but bearing small fangs. In the Bon tradition, similarly to Tibetan Buddhism, wrathful deities can be emanations or represent local gods and sprits. In Hindu traditions, gods and goddesses can appear fierce, holding many weapons meant to overcome demons.

The Yuan dynasty (1271–1368) is the branch of the Mongol Empire in Asia. In 1260 when Qubilai Khan declared himself Great Khan, his realm included Mongolian, Chinese, Tangut, and Tibetan regions. In 1271 emperor Qubilai Khan proclaimed the Yuan dynasty on a Chinese model, employing Tibetan and Tangut monks. Tibetan Buddhism played an important role in the state, establishing a political model that would be emulated by later dynasties, including the Chinese Ming and Manchu Qing dynasties. The Mongols were major patrons of Tibetan institutions, and many Mongols converted to Tibetan Buddhism, though their interest declined with the fall of the empire.