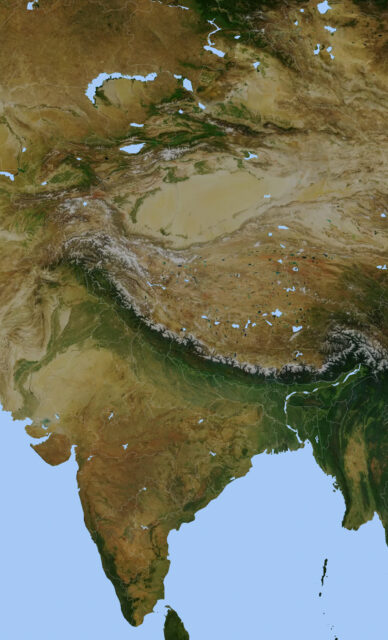

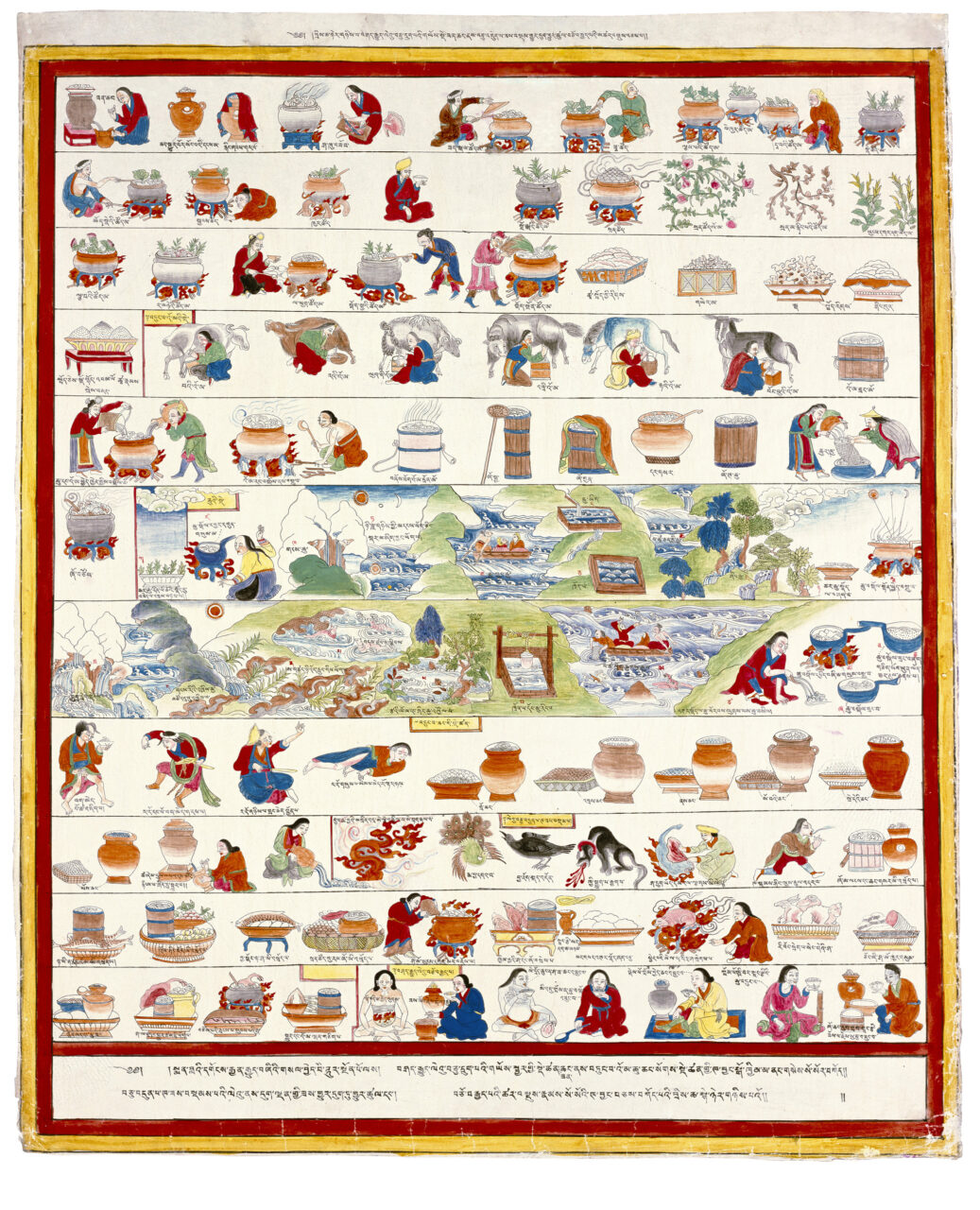

Caste is a traditional system of social division in India and Nepal. The English word “caste” combines two Indic concepts. “Varna” refers to an ancient fourfold division of occupations into priests (brahmins), warriors, farmers, and laborers. In Nepal, the caste system is unique and applies to both Hindu and Buddhists. Like the Hindu brahmins, Buddhist Vajracharya priests and Shakyas are considered the highest caste among the Buddhists, with similar correlations to other social occupational groups. Udas or Uray caste is formed by hereditary merchants and artisans. They are known for their part in the development of industry, trade, arts and culture, and the trade with Tibet. The other ethnic groups traditionally existed largely outside of caste. The caste system was officially abolished in Nepal in 1963.

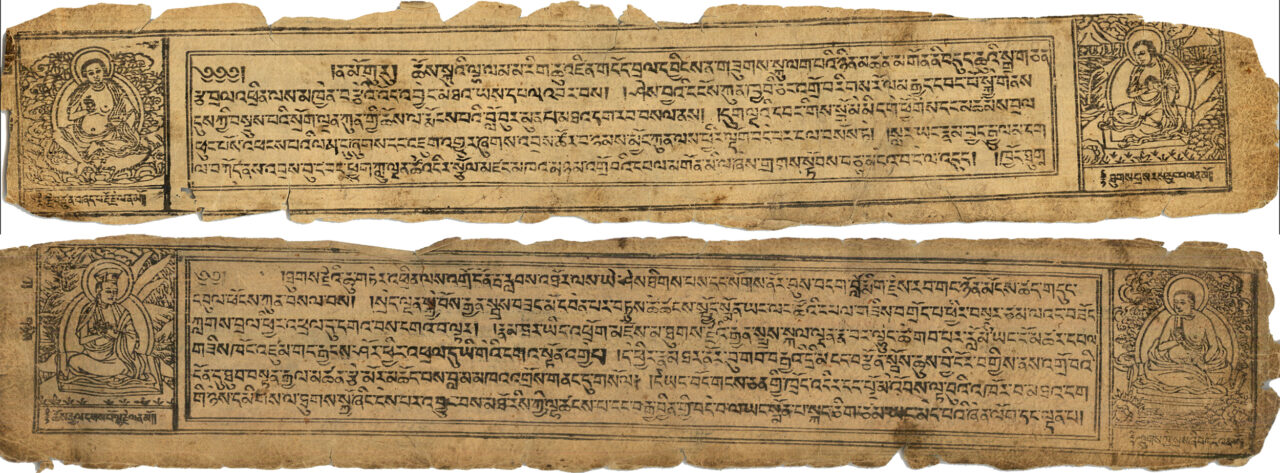

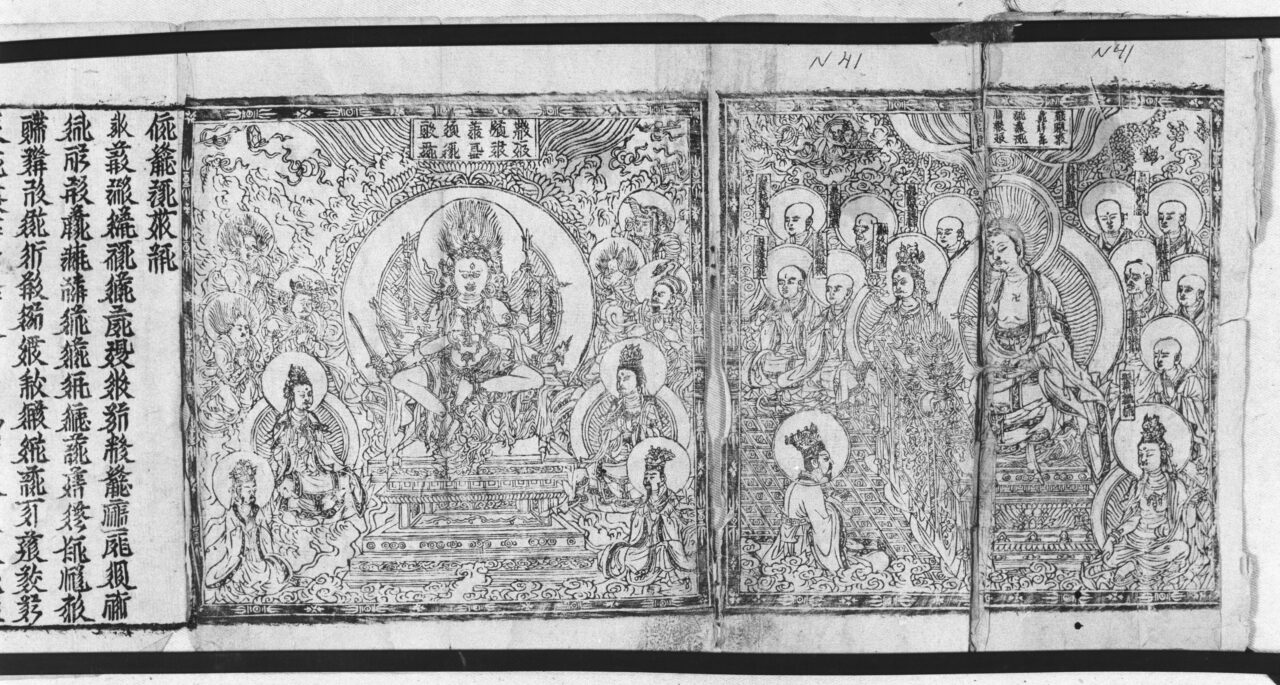

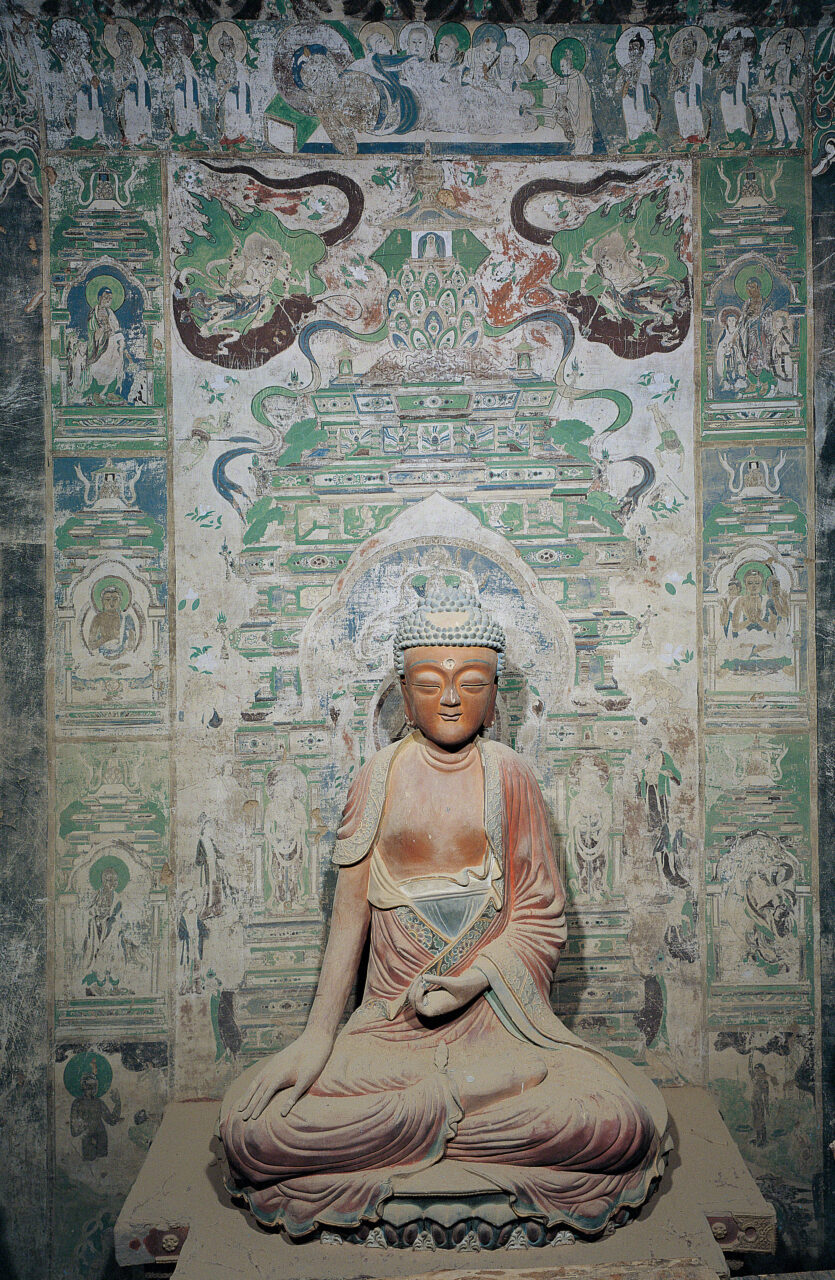

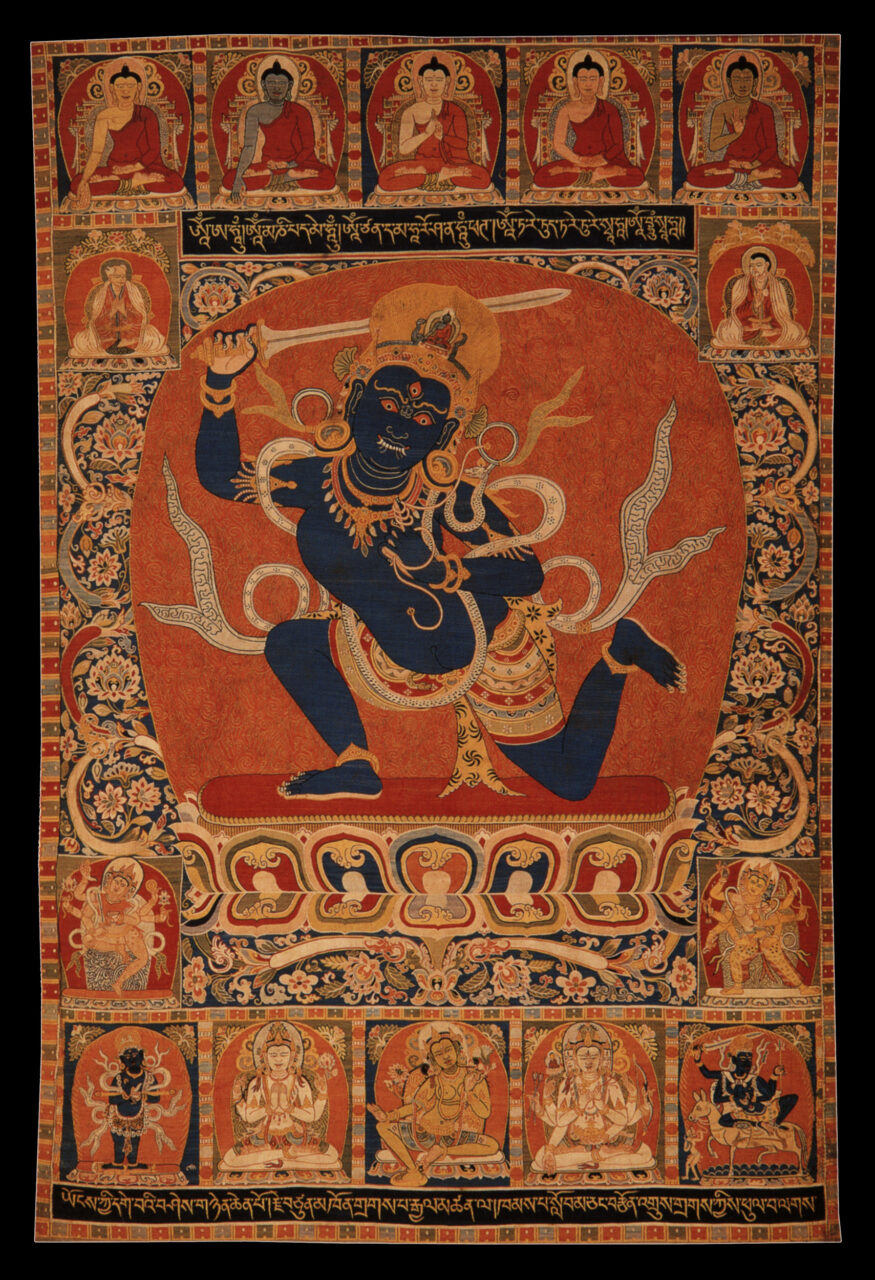

In most Asian religious traditions, when an image of a deity is made, it must be made sacred (“consecrated”) by inviting the deity to inhabit it. A variety of rituals can be involved in this, including dotting the image’s eyes, visualizing the descent of the deity into the image, writing mantras on the back of a thangka, or placing sacred texts and mantras inside of a statue.

In Buddhist context, donor is a person who contributes to or commissions a religious work of art. This act is intended to increase merit on behalf of the benefactor and is dedicated to the benefit of all. It is also usually done for a specific purpose, such as longevity, prosperity, or well-being; to advance religious practice; or to ensure a good rebirth of a deceased relative, teacher, or friend. A similar practice is also known in Hinduism and Bon.

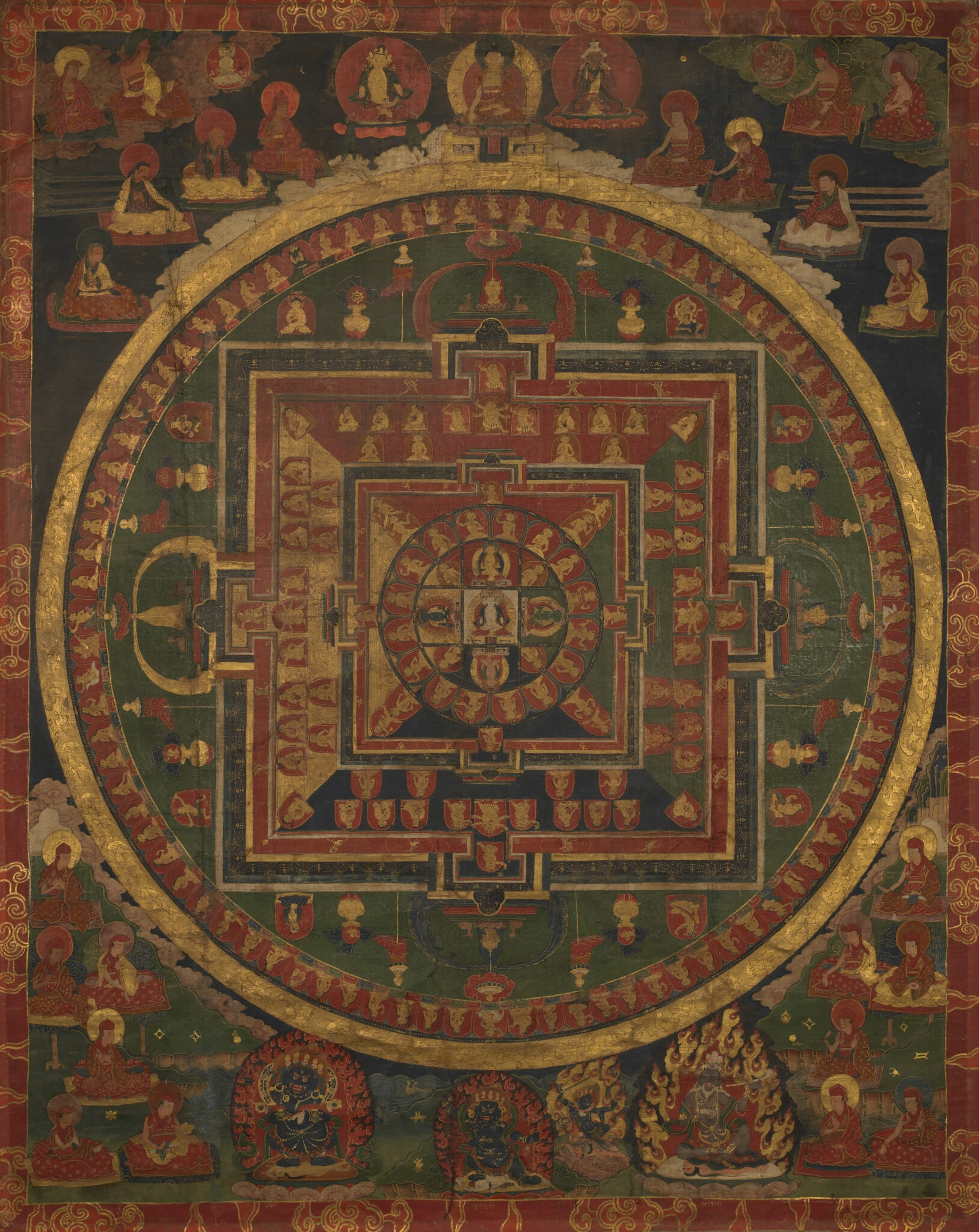

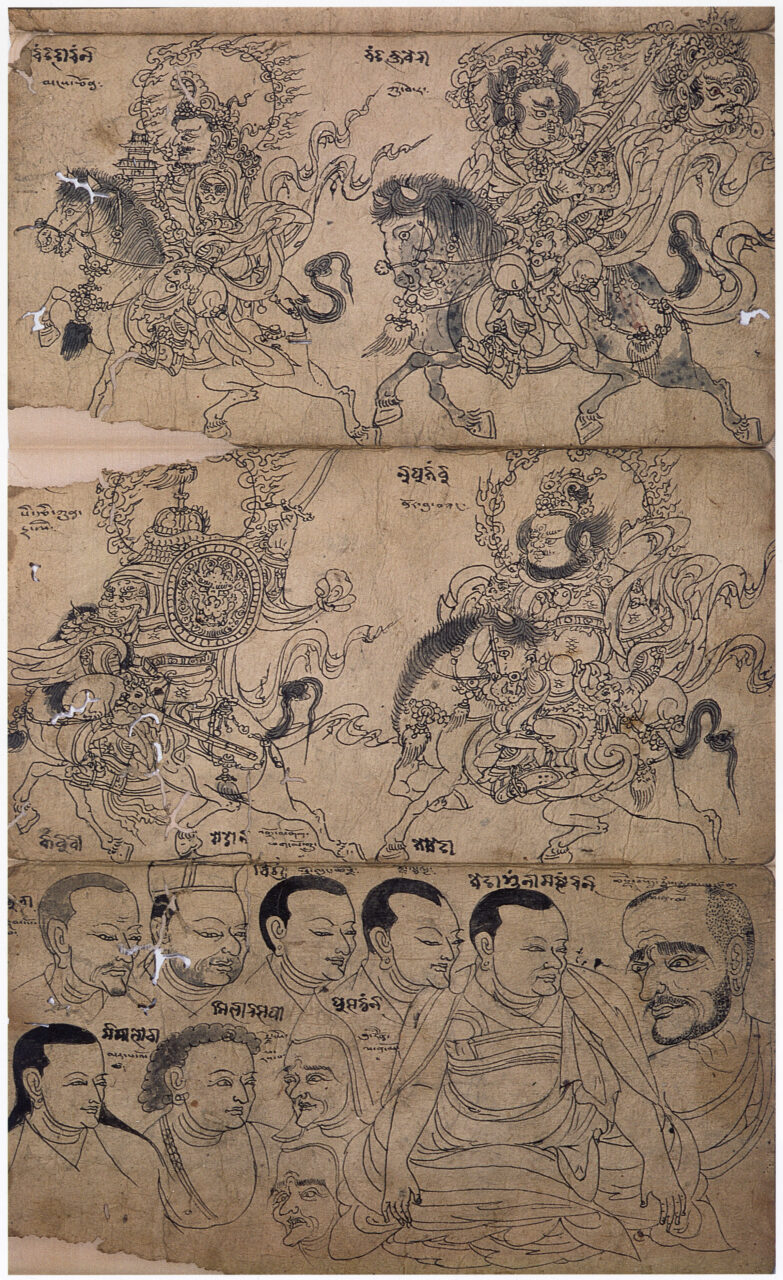

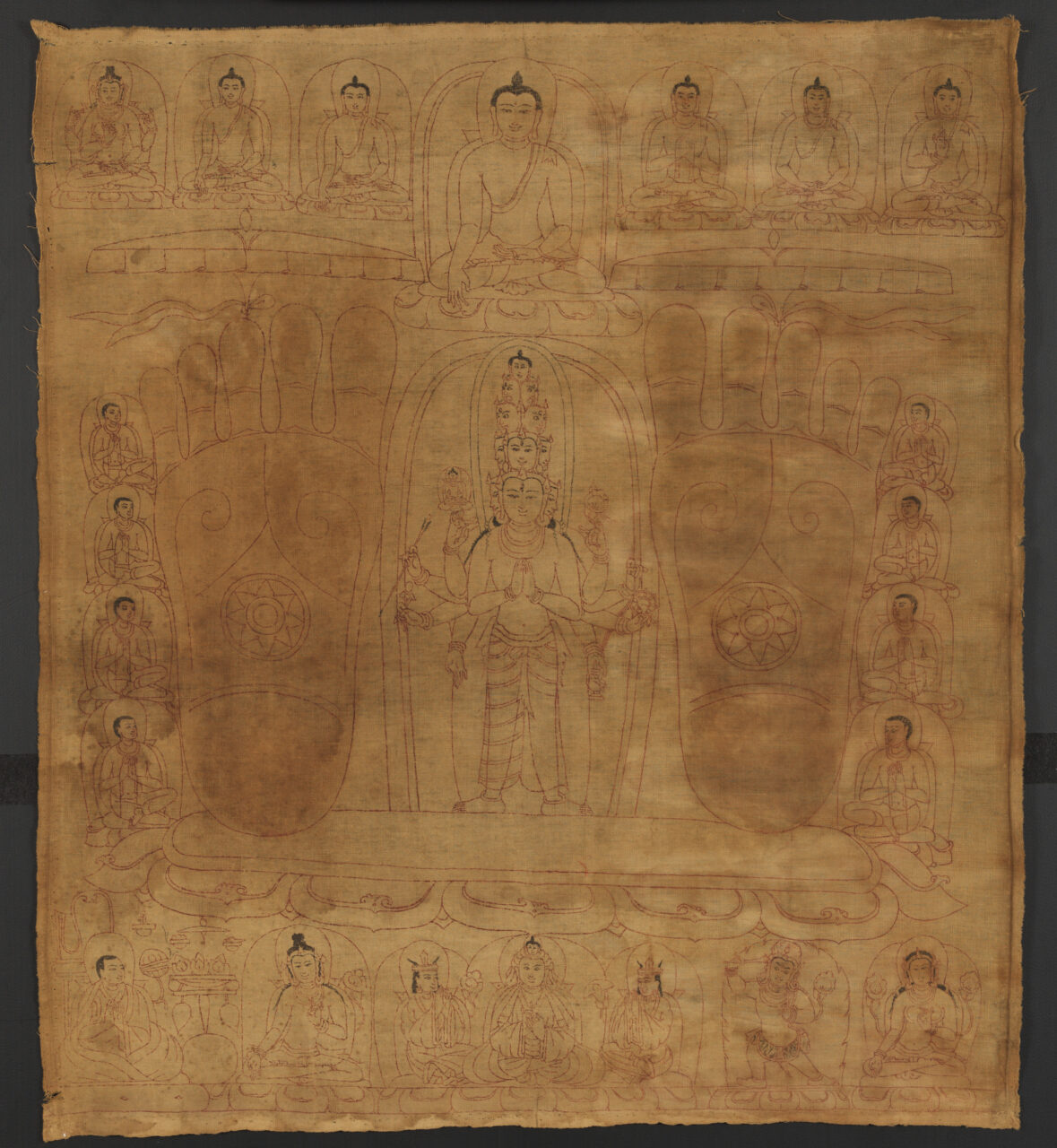

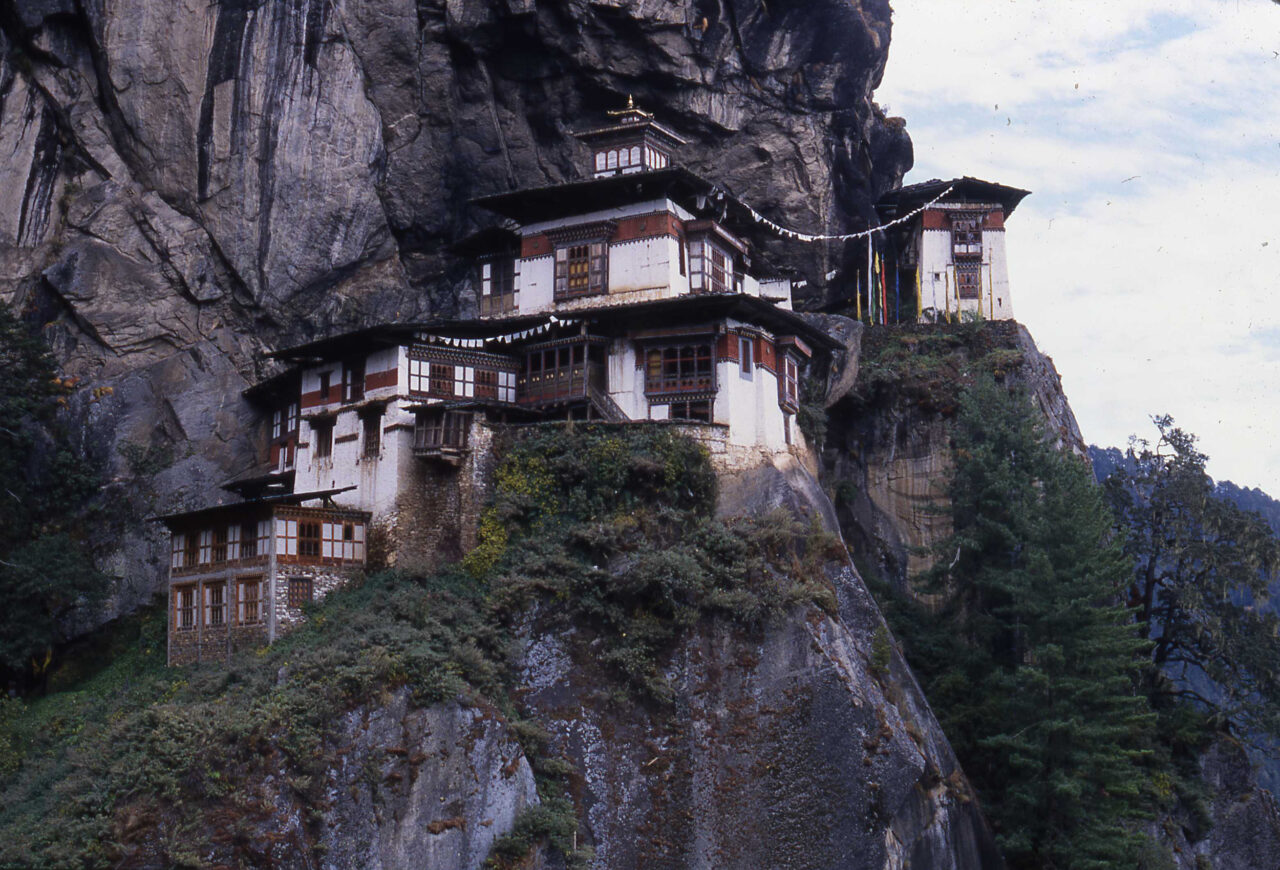

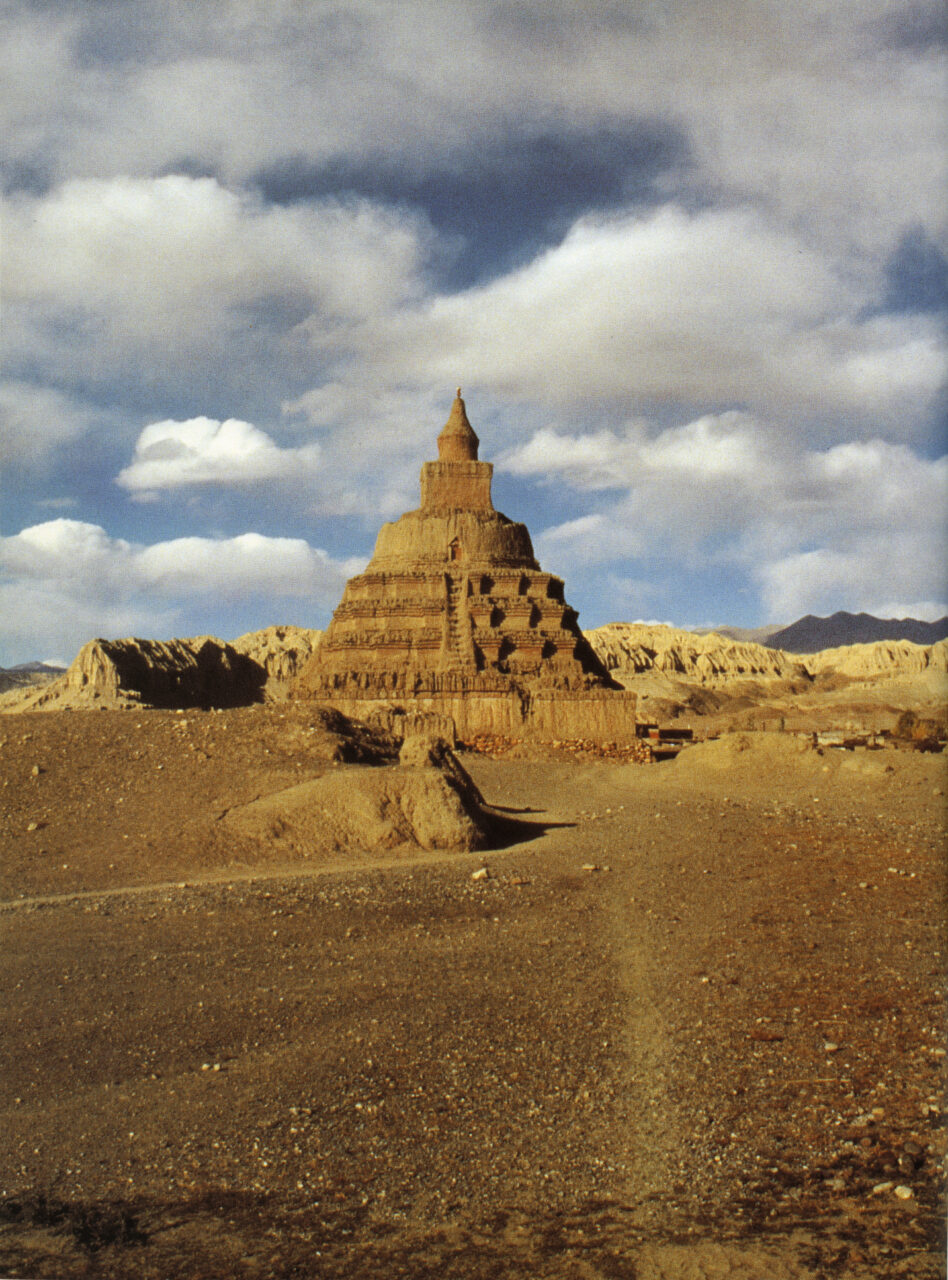

In Vajrayana Buddhism or Bon, a mandala refers to a cosmic abode of a deity, usually depicted as a diagram of a circle with an inscribed square that represents the deity enthroned in their palace, surrounded by members of their retinue. Mandalas can be painted, three-dimensional models, architectural structures, such as temples or stupas, or composed as arrangements of images within a temple. The instructions for creating and visualizing mandalas are usually found in ritual texts, such as tantras and sadhanas. Mandalas can be used in initiation ceremonies, visualized by a practitioner as part of deity yoga, consecrated and used to represent the divine presence within ritual space, offered to the deities as representations of the entire universe. A similar concept in Hinduism is a yantra.

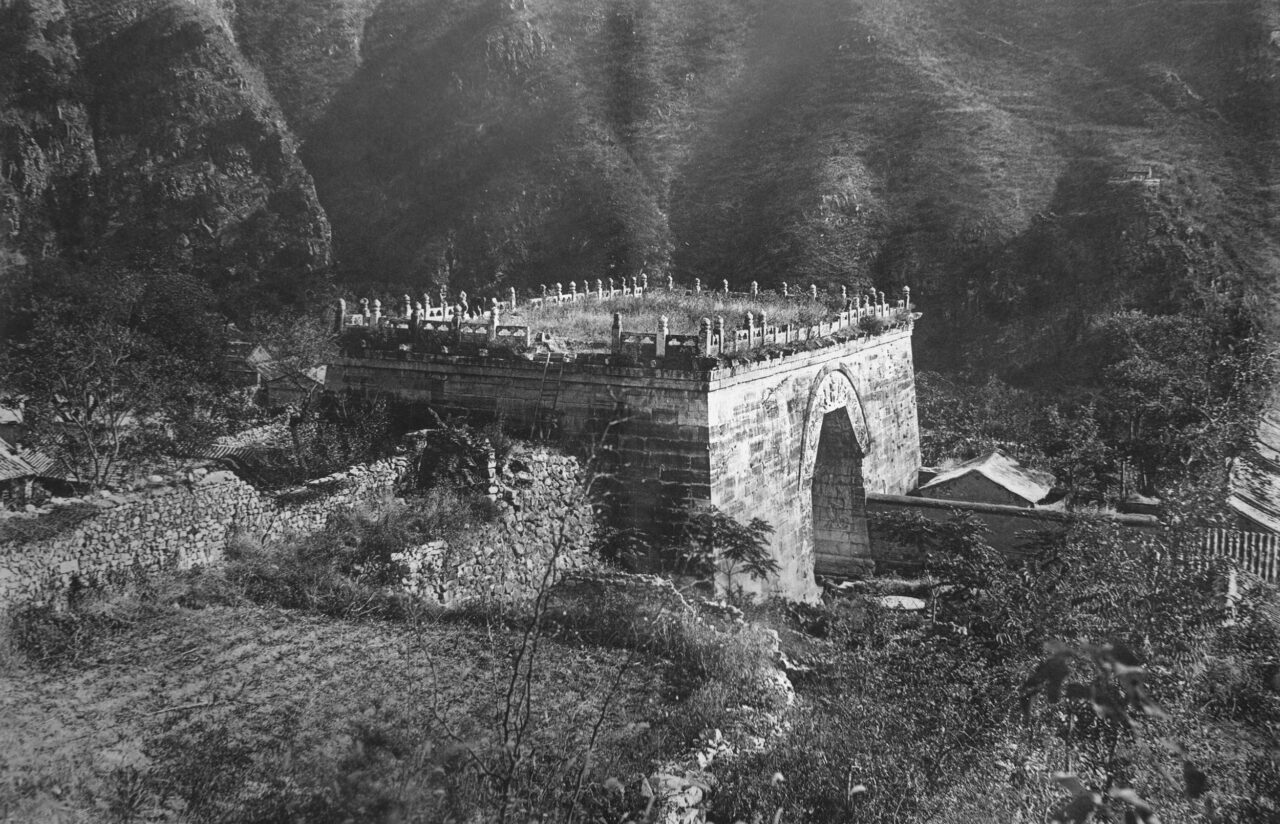

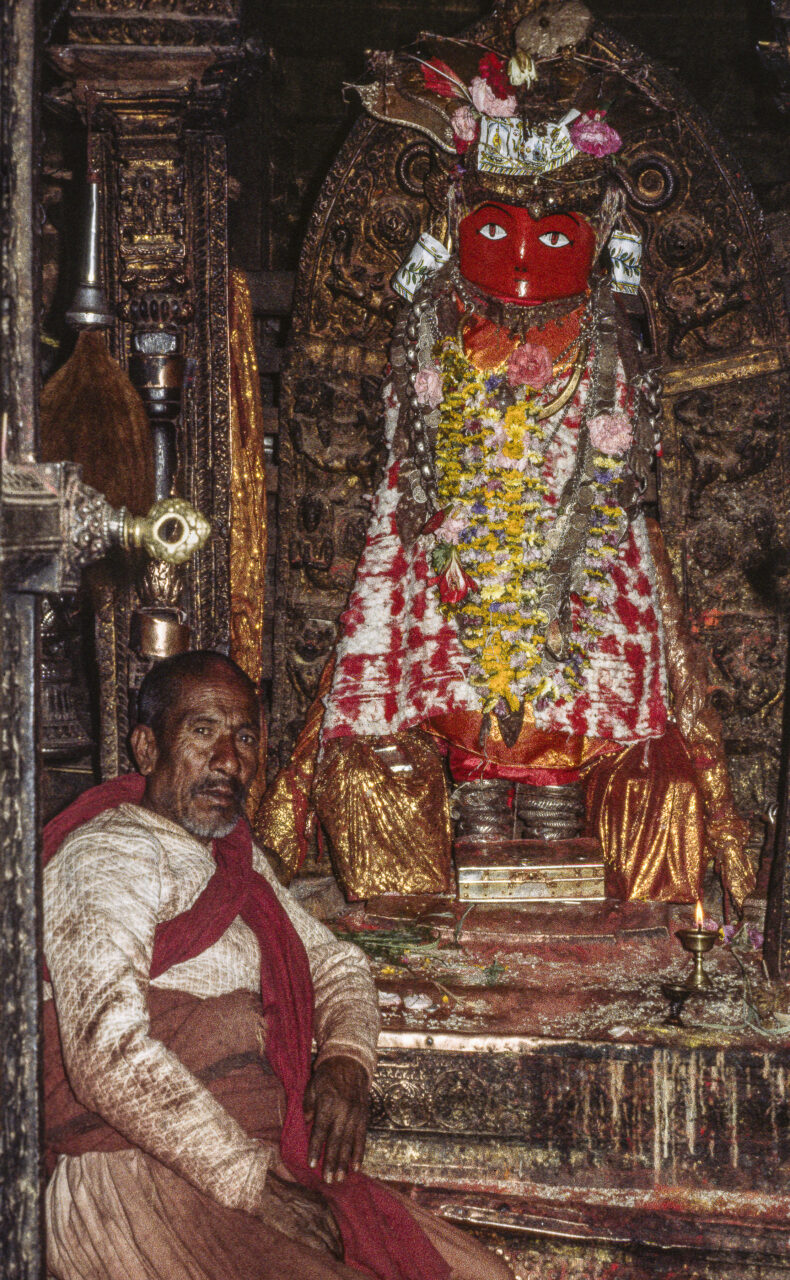

The Newar People of the Kathmandu Valley of Nepal retain the unbroken traditions of Mahayana and Vajrayana Buddhism south of the Himalayas, preserving many ritual practices and Sanskrit-language texts that have been lost elsewhere. Celibate monasticism is no longer practiced among the Newars, but instead Buddhist ritualists are divided into two castes. One is the Shakyas, temple-priests who maintain ancient urban monasteries (Newar: bahas, bahis) as places of worship. The other is the Vajracharyas, tantric specialists who perform rituals at communal festivals and important life events. The Svayambhu Stupa is the most important ritual center for Newar Buddhists and the center of the Kathmandu Mandala. Today many Newars also practice Theravada and Tibetan Buddhism.

In Vajrayana Buddhism, a Vajracharya is a general term of respect for a teacher or tantric master who gives teachings and abhisheka initiations. In Newar Buddhism, Vajracharya is a specific caste of non-celibate ritual professionals, who make a living performing tantric rituals on behalf of members of the community.